|

We walked into the bar. "Have a seat, Charles," my father said, pointing to a table. When the waiter arrived, my father stood, while beaming with pride, he introduced me to his friend, "George, this is my son; Sergeant Bissett. He just returned from the war with Iraq."

Having just returned from a war, I think I can safely to say that war is one of the most disconcerting experiences a person could undergo. I had been in combat; fought in the Persian Gulf War. Little did I suspect how shallow my experience had been compared to my father's combat experience. Nor did I realize the long-term toll his war did have on not only him, but would even have on his unborn family.

"Hello, George." I said, as I stood up and extended my hand. "You can call me, Charlie." I was at home in civilian cloths, and felt a little self conscious about being paraded around as if I had really done something extraordinary.

Dad was so relieved that I had returned home. Dear God, only a month before, the politicians and press were telling the public to expect forty to fifty thousand American dead. My father had heard that the Iraqis had the fourth largest Army in the world. He also knew they were battle hardened combat veterans. Although he didn't show it, I knew there was a lot more going on within him that he was not revealing. I had learned from my stepmother that during the war, he had been almost obsessed about me getting killed.

My father had fought during all three years of the Korean War. Some of my earliest memories of my father were of being woken up in the middle of the night by my father screaming in fear. I remember one time, jumping out of my bed and running into my father's room. I found him kneeling, huddled against the wall by his side of the bed. He was slack with exhaustion as sweat covered his brow and dripped down the side of his face. On the floor was a mess were he had puked his guts out.

As a child, I remember running over to my mother as she turned on the lights. I grabbed on to her. "Mommy, mommy... what's wrong with daddy!" I cried. Then I looked up into her face and saw blood running down the side of her face. "Mommy! You're bleeding! Mommy, are you okay? Mommy, what happened?

"It's all right, Chucky," she intoned as she led me out of the master bedroom. "Daddy just had a bad dream."

"But Mommy, you're bleeding?" I asked as she led me into my bedroom. "What happened? Did daddy hurt you?"

"Shhh..." she whispered with a finger over her mouth as she tucked me back into bed. "It was an accident, Chucky. Daddy had another dream about the war. He thought the cannon balls were falling out off the sky. He was only trying to push me out of the way so I wouldn't get hurt. And, what happened was, that I ended up hitting the nightstand. But, daddy was only dreaming this.... He didn't mean to hurt me."

I didn't really understand what was happening to my father. Unfortunately, I wasn't the only one who didn't understand. Back then, psychologists were still coming to grips with combat fatigue, which some soldiers experienced just after a battle. No one was aware that war had adverse long-term psychological affects, also. No one, not even my father suspected that what happened to him would create a barrier between him, and his family. My father's bad dreams had been going on all my early life. As a toddler, I didn't know any different. I just accepted that they were a part of my father's life.

It wasn't until after the Vietnam War that society did any real investigation into what was later called, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. By the early 1970's, the dreams had subsided. I am sure, he was too embarrassed to tell anyone about the dreams, and the way he had behaved during them. Furthermore, my father worked for a government contractor and held security clearances. He couldn't afford to be labeled as mentally unstable, or he would have lost his livelihood. As a result, my father never did get any formal help in dealing with the demons that haunted the shadows of his memories.

As we stood in the bar, George shook my hand. "Glad to see you made it back in one peace." he said. "What'll you have?"

We sat down, once the bar tender left. "So Dad, what do you think? We both went into combat as artillery men, and we're both combat alumni of the same division?"

He grinned, recognizing the irony of such a coincidence. Then he launched into a conversation that I had never expected. "I never really have told you about what happened to me during the Korean War. I don't like to talk about it much. To most people they would only be exciting stories. But, now that you've been in combat, I think you can understand."

"Charles, I was part of the advanced party that was first sent to Korea. It was called, "Task Force Smith." It was named after our commander, Colonel Smith. Originally, I was stationed in Japan. One day the sergeant came in the barracks, and said, "Pack your gear, boys. We're going on a plane ride." The next day, we found ourselves in a little village called, Osan."

"There were only about four hundred and fifty of us, but we weren't concerned. We thought, as soon as those guys see that we're Americans, they wouldn't dare try to fight us."

"Charles, we didn't know.... I was only nineteen. I never suspected how bad it was going to be...."

"Our light infantry battalion was hit by three armored regiments. We tried to fight, but our equipment was a bunch of outdated World War II stuff. We were trying to stop Russian T-34 tanks with 30 caliber rifles. And, those damn bazookas; the rockets just bounced off the sides of the tanks." My father paused for a second. He had that faraway look, as he relived the memories. "Once they hit us, they ripped through us in less than fifteen minutes. They just ran us over, while we were still in our foxholes. I don't even think the first group even realized we were there as they passed on down the road.

|

|

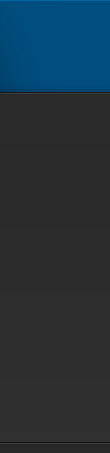

This was PFC Charles P. Bissett, my father during the Korean War, around the end of his first year of combat. He was an infantry soldier that was later assigned to an artillery battalion as a field phone lineman for a forward observer team. He had a reputation for being good with a pistol in a close fight. He was about 19 or 20 years old in this photo. During the war, he fought with the 24th Infantry Division |

|

"My sergeant came up to me in the middle of the fight. He ordered me back to the village, and told me to get on the trucks. I never saw him again, after that. When I got to the village, I hopped on a truck. There were only three trucks left. We spent the next two days trying to get back to friendly lines around Pusan. Only about forty of us got out of there." (In less than 20 minutes a battalion with an attached howitzer battery, of four hundred and eighty men, was reduced to about half its size scattered around the Korean country side or captured and held as POWs for the remainder of the war. The massacre of Task Force Smith has become for the U.S Army, the iconic example of a neglected force being pressed into battle.)

"I remember later, at Taejon; we were surrounded." he began again. "It got nasty, really nasty. We were fighting house-to-house, hand to hand. The Communist, they weren't really well equipt. They would charge at us in squads of eight or nine men. Only the guy up front would have a rifle, the rest carried sticks. They'd come at us in a line, with the guy up front shooting. We would shot the guy in front. As he'd go down, he'd simply pass the gun to the next guy, who would continue to carry it forward."

"Even if we shot five or six of them, there was still someone to carry that rifle forward. They'd eventually swamp us, and there wasn't much we could do."

"Charles, I really thought I was going to die that day. During that fight, I bumped into (Major) General Dean. He was the division commander. I followed him around for a while. We got separated. Later, he got captured. Everything seemed to be falling apart around us. We were trapped at the bottom of the peninsula, and there wasn't any place to retreat, except the Pacific Ocean."

"I was so scared, running around shooting at the Communists and trying to find a safe place to hide. That's were I got injured the first time."

"General Dean ordered his headquarters security team to block the communists from getting a position on the main road coming into town. It would have been a straight shot for a tank to hit the trucks trying to get out on the other side of town. That would have caused a bottleneck that would have left the division trapped."

"This MP sergeant put me at the end of an ally. He gave me a bazooka, and told me not to let them get past. The next thing I know, there's this big tank coming up the ally."

"So, I picked up the bazooka and felt someone behind me load a rocket. I looked behind me, and there was General Dean yelling, shoot son, shoot!"

"The tank and I both fired at the same time. I made a direct hit, and blew the tank up. His round hit the brick wall next to me, and I got a bunch of shrapnel in my foot."

I don't know how I ever got out of there, that day. By the time it ended, I was too exhausted to think straight. I was injured and couldn't keep up, so they left me under a set of porch steps. I heard that the General and the rest of the team was captured shortly thereafter."

"Sometimes, you get it when you least expect it. There was this guy, Walter. We were friends. We hung out together. One morning, the Communists fired an artillery air burst over our camp. At breakfast, I found him still in his sleeping bag. A peace of shrapnel had caught him in the chest. It slipped between the opening in his flack vest and killed him. He looked so peaceful, just lying there as if he were asleep. Who would have ever guessed, he got it from a stray piece of metal."

"Cochran, he got it bad. An artillery round landed in the foxhole were he was hiding. There wasn't anything left of him. We just filled in the hole, and put a cross on it."

In all the times that I had heard my father mention the war, I had never heard him mention the details of any battle in which he fought. I had never heard him mention the names of anyone he had fought beside. I had never heard him talk about the emotions he had experienced in battle. I knew he had two Purple Hearts, and a Bronze Star; but this was the first time he had ever mentioned how he had earned them.

I recalled once discovering a box with a bunch of black and white photos. They were my father's, from the war. He let me look at them, but he never said much. Later after I joined the Army, my father shared with me a few antecedents from the war. Yet, these were only meant as tips to help me in dealing with the Army. He had never told me about his personal impressions from his experiences in Korea.

For three hours we sat at that table while my father talked. He hardly touched his beer. I could only listen as he spoke.

Finally, I understood why he never talked very much about the war, before now. He wasn't just telling me war stories. He was showing me how his experiences had become integrated into the very fabric of his soul. During three years of relentless fighting for his life, he had lived a lifetime. Secluded along with his experiences, were all the emotions that had become branded into his psyche; the confusion, the horror, the grief, the anger. These companions were as real to him as the undrunk beer on the table.

|

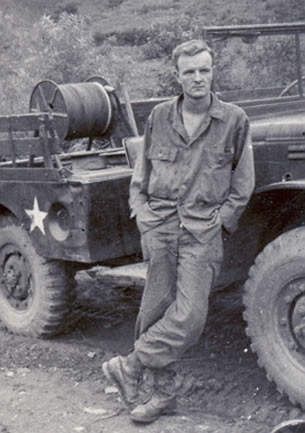

| SGT Charles W. Bissett doing radio watch during the Desert Shield phase of the Persian Gulf War. At this point, he was the Crew Chief of an MLRS rocket launcher. In this photo he is 37 years old. During Desert Storm, he fought with the 24th Infantry Division, also. |

|

|

The forty years since then, had done almost nothing to lesson the intensity of that experience.

My father's stories were too personal; too intimate an experience for him. He could not demean himself by pandering them in front of people who couldn't relate to what he had been through. This included, even his children. His memories from the war intruded into his perceptions of the present. It caused a distorted emotional coloring to anything he was doing at the moment. It had interfered with the relationships he wanted to have with his children. Just being his oldest son was not enough to qualify for admission into this corner of his soul.

Now, I sat at the table in muffled shock. I felt as if a light had been turned on within my own soul. It explained what had been a real enigma about my father's relationship with me. Somehow, we had always been distant from each other. Now, I understood why. I realized that because of his secret burden, he had never been able to make a total connection with anyone in the family. His spirit was still held captive in the past.

As he talked, I realized that there was no way that my four-day war could be compared to the three years he had endured. Yet, I couldn't tell him that I didn't feel worthy to hear his story. Regardless of my unworthiness, my father needed to tell me what had happened to him in Korea. He needed to break free of the terrible hold those memories had on him. This final unveiling of his past, and sharing who he was, at last gave him a chance to erect that missing

connection with at least one of his children, and with the present.

|